Alive as You or Me (2014)

6 photographs, all 6x8in, plus text and YouTube links

I. In his Confessions, Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430 AD) introduces us to a God that’s “stable, yet incomprehensible; unchangeable, yet all-changing; never new, never old; all-renewing, and bringing age upon the proud, and they know it not; ever working, ever at rest…” It’s a conception that undergirds Augustine’s ongoing internal flux and manifests a “frame,” as he says, within which to imagine his life experiences. In his Confessions, then, eyes attuned to the space encompassed by that frame, Augustine begins to pass through life from infancy to boyhood and beyond—a tumbleweed, picking up ideas and memories, sin and redemption, along the way.

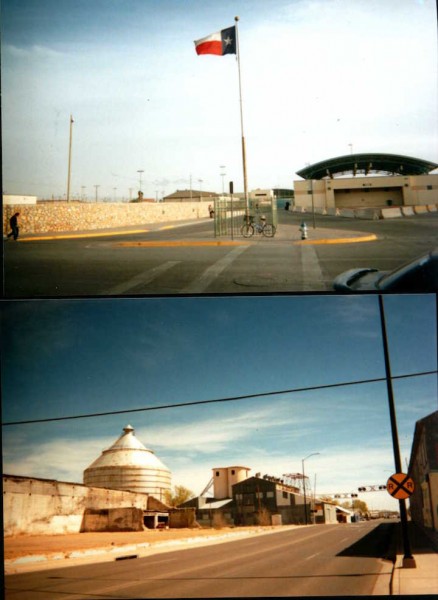

II. There are parts of West Texas where it’s so flat that, driving along the highway, you can see landmarks 30 miles in the distance, maybe more. Where-you-are and where-you’ll-be collapse onto the same point in time and space. Make sure your tank’s full, though.

III. John Wesley Hardin killed a man for snoring, they say, but he was also a friend to the poor. A controversial figure, in other words, Hardin might be considered “stable, yet incomprehensible.” When Dylan sings that Hardin(g) “traveled with a gun in every hand,” one might imagine the outlaw passing through the landscape—known (“wanted”) but unknowable (fugitive), “ever working, ever at rest”—like Shiva, sprouting new gun-toting hands at will.

IV. “For a sentence is not complete unless each word, once its syllables have been pronounced, gives way to make room for the next.”—Saint Augustine of Hippo, Confessions.

V. One wonders whether the desert’s climate has any effect on the efficacy of power lines—if the extreme temperatures slow signals down, or if the dry air speeds them up, or if, most probably, it’s all the same. One might assume, though, at the very least, that the average signal out there travels further than those in other places; the telegrams they sent to call for the head of however many so-and-sos must’ve pierced more blue skies than one could imagine before reaching their final destination.

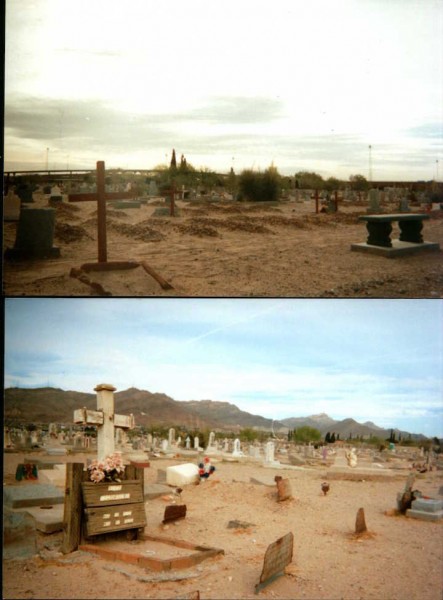

VI. John Wesley Hardin was shot dead in the summer of 1895 by Constable John Selman, Sr. After being pardoned and released from prison the year before, he had settled in El Paso, and his body lays there still—buried at Concordia Cemetery. His tombstone, modest in itself, is re-imprisoned: surrounded by an outsized cage, as though to keep his dormant criminal bones from escaping. Indeed, the way the shining black cage imposes upon the environment—otherwise white, dry, lifeless in the most human sense—suggests its inhabitant’s vitality. Is John Wesley Hardin alive as you or me? Might he rise out of the dirt, transgress the thresholds of the cage and, soon after, the country? This world is not his home; he’s just passing through.